Spotlight on Legge Lane: Part Two

Reading Time: 3 minutes

The Jewellery Quarter was home to some 30,000 workers by 1914. In the late 1800s, as family firm Alabaster & Wilson was getting established, space was at a premium as businesses and independent artisans made use of every piece of land…

Prosperous merchants and professionals initially moved to the St Paul’s district to escape industrialisation. The site on a hill was something of a rural idyll. But not for long!

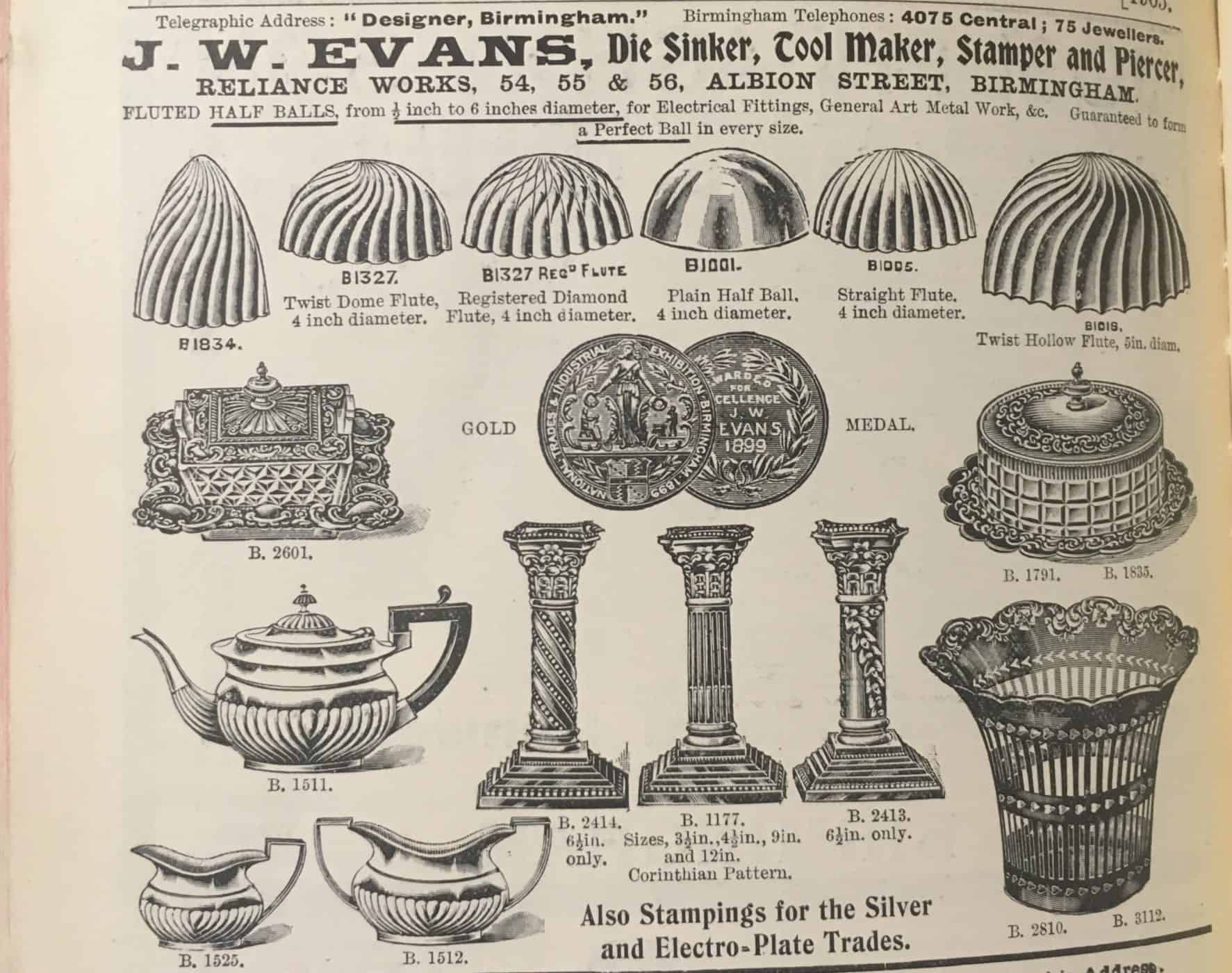

Garden workshops and attic conversions became increasingly common as businesses expanded and domestic houses were put to use. A good example is the expansion of J.W. Evans. Jenkin Evans originally lived at No 54, before buying up the adjacent 55, 56, and 57 Albion Street to expand his manufactory producing silverware stampings, dies and patterns at the height of Edwardian demand for fashionable tableware.

In neighbouring streets, workers’ houses were built as back-to-backs.

By the end of the 19th Century the Jewellery Quarter was becoming more and more crowded – nobody seemed to move out of the district as each skilled occupation depended on the next in the ‘jewellery chain’ of production.

Garret masters like Jenkin Evans, also known as small masters, were the engine room of the Birmingham boom – producing thousands of trinkets, or ‘toys’, which led to Birmingham becoming known as the toy shop of Europe.

Cheap gold from California and Australia, coupled with lower standards of gold alloy and new electro plating technology, created a rapid expansion of the jewellery industry. Suddenly, jewellery was more affordable and so new markets emerged, impacting on the scale of production.

People flocked to the Birmingham to find work from across the UK and as far as France, Poland, Germany and America.

We see evidence of this in the 1891 census, produced just after the founding of Alabaster & Wilson. A David Herman, 46, of Morez, France, is listed at 31 Frederick Street. He was a diamond merchant, and lived with his wife Leorna, their two children, and two servants.

At Number 22 lived Isaac Summer, 60, a Polish jeweller’s agent, with his wife Amelia and four children. At Number 27 we find Adolph Cohen, 62, of Hamburg, Germany. He had a wife, Juliana, and five children listed in the previous census, though by 1891 they had all flown the nest. At No 43 was Abraham Cohen, an American merchant originally from Germany, who met his wife Rachel in New York. They had two children and a servant.

Other families on Frederick Street included: a coach saddler Francis Hewitt, who lived at No 23 with his wife, five children and a servant; George Shenton, a goldsmith, who lived at No 32 with his wife and four children; William Goodwin, a silversmith at No 4, who lived with his wife and five children, and Walter Pinter, 40, who was a gold ring maker. He had a wife and eight children.

There were brass founders, pin pointers, burnishers, engravers, gold beaters, silversmiths, button stampers and printers. Robert Thomas was a cabinet maker working from his garden. William Davis used his scullery to make saddle nails.

Nearby Vittoria Street housed numerous large working families, and many took in lodgers to make ends meet.

A typical house was 4 Back 13 (indicating a back-to-back). George Gleadall, 37, an iron and steel polisher lived there with his wife Emma, their four children and lodger Bridget Burns, a 60-year-old widow.

Nearby, a tale of poverty and ill health unfolds…

At 3 Back 24 lived John Steward, listed as ‘blind and paralysed’. His wife Mary could not have supported the family as a paper bag maker, so the couple’s daughter Isabella, 17, a warehouse girl; Robert, 16, a brass dresser; and John, 12, a baker’s boy, were all out working. There were two other children under ten, and a sister-in-law, Laura Allen, who maybe helped look after John.

This family lived only yards from the wealthy merchants of Frederick Street! One of the most striking things about the history of the Jewellery Quarter has to be the close proximity of wealth and poverty, mass industry and individual labour, ingenuity and the basic will to survive.