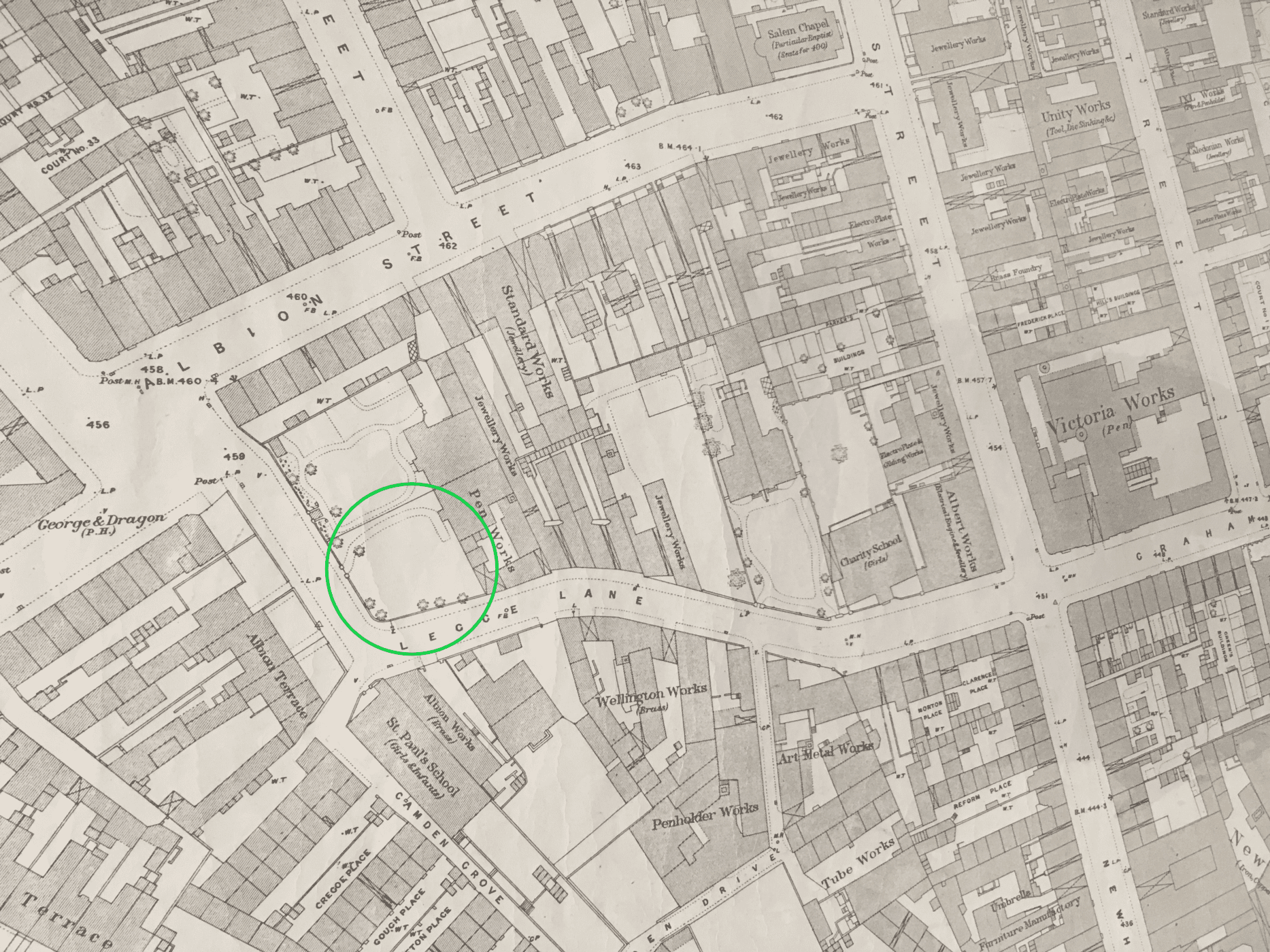

Spotlight on Legge Lane

Reading Time: 4 minutes

The Jewellery Quarter Townscape Heritage project aims to promote the heritage of the area through events, activities and research. Writer Louise Palfreyman has been in the archives finding out what the neighbouring businesses of this unique district reveal about working life in the late 1800s.

For nearly 130 years, Alabaster & Wilson produced fine jewellery from 9 – 11 Legge Lane in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter.

When Arthur Alabaster and Thomas Wilson were searching for a base for their fledgling firm, they knew the Jewellery Quarter was the place to be.

Home to a breathtaking number of factories, manufactories and independent traders, the district was alive to the sound of industry. Although Birmingham had made a name for itself manufacturing trinkets, Alabaster and Wilson were determined to challenge the perception that fine jewellery could only be found in London’s Hatton Garden.

The firm started life on Vyse Street before moving to their newly-built factory at Legge Lane in 1890-91 where they were listed as ‘goldsmith and jewellers’; and there they remained, producing fine sporting jewellery until 2017.

A picture of Legge Lane emerges from an 1890 trade directory, which shows the concentration of industry in the surrounding Victorian buildings. Here was a thriving blend of converted houses, factories, and specialist works devoted to the production of jewellery and metalworking. Many of the original machines are still in use today!

At 1 Legge Lane we find John Morrison, a Scot who moved to Birmingham to find work in the pen trade, as manager of a ‘steel pen works’. He lived with his wife, seven children, and two servants. Census records often indicate the financial circumstances of a family, through the presence of servants, or, at the other end of the scale, the fact that the children were working before their teens.

At Number 5, William Devenport & Sons are listed as wedding ring makers. They later moved to Warstone Parade and their silver makers mark is still found in antique dealer listings.

At Number 6 Albert Rupert Middleton, an electro plate manufacturer, shared premises with John Taylor, a jeweller, and Woolley & Co, military ornament manufacturers. Electro plating was invented in nearby Newhall Street, and allowed mass marketing of cheaper goods, typically cutlery and jewellery, though the inventors Henry and George Elkington also made the Wimbledon Ladies Singles Trophy.At Number 7 Legge Lane we find Kleenquick Co, manufacturers of a labour-saving boot cleaning machine, and George W. Hughes, a steel pen maker.

A Kleenquick advert from the time proclaims:

‘Every house should have this new invention! Boots and shoes cleaned better, with half the trouble in half the time!’

Henry Collett is at Number 12, employed as a metal stamper, and at Nos 15-16 is Ernest Hawkins, another electro plate manufacturer, indicating the rapid expansion of this Birmingham-born process.

St Paul’s School is at Number 18, along with George Pritchard, a shopkeeper. Next door at Number 19 is brass founder F.A. Harrison. More brass founders, W. Walker, Son & Co can be found at Number 23 and at Number 25 is Edward D. Robinson, pen holder maker and George Henry Twigg, a paper fastener manufacturer.

Nearby were beer retailers, dressmakers, a greengrocer, a dairy, letter cutters, gun barrel makers, glass button makers, carpenters and a baker’s, showing just how many businesses supported life in the Jewellery Quarter.

An additional wing was added to the Alabaster & Wilson factory by 1900, and by 1946 there were more than 20 craftsmen and women employed.

Legge Lane is just off Frederick Street, where the Albert Works (today’s Pen Museum) produced pen nibs in a Renaissance-style factory complete with Turkish baths. The baths were powered by recycled steam from the works, and housed luxurious leisure facilities to rival any modern-day spa.

The Albert Works stood opposite Joseph Gillott’s Victoria Works, which employed 600 people, mainly women, in the pen trade. These flagship factories were among 129 in Birmingham that once manufactured a staggering 75 per cent of the world’s pens.

By 1866, 7,000 people were employed in the jewellery and metalworking trade in Birmingham. This rose to 30,000 by 1914. So at the time Alabaster & Wilson were getting established, business really was booming in the district, and the streets would have been thronging with locals and merchants from abroad who had come to make their fortune in Birmingham.

Read part two tomorrow!